Seanchas Agus Litríocht Na nGael

The background to the indigenous literary traditions of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man.

Introduction

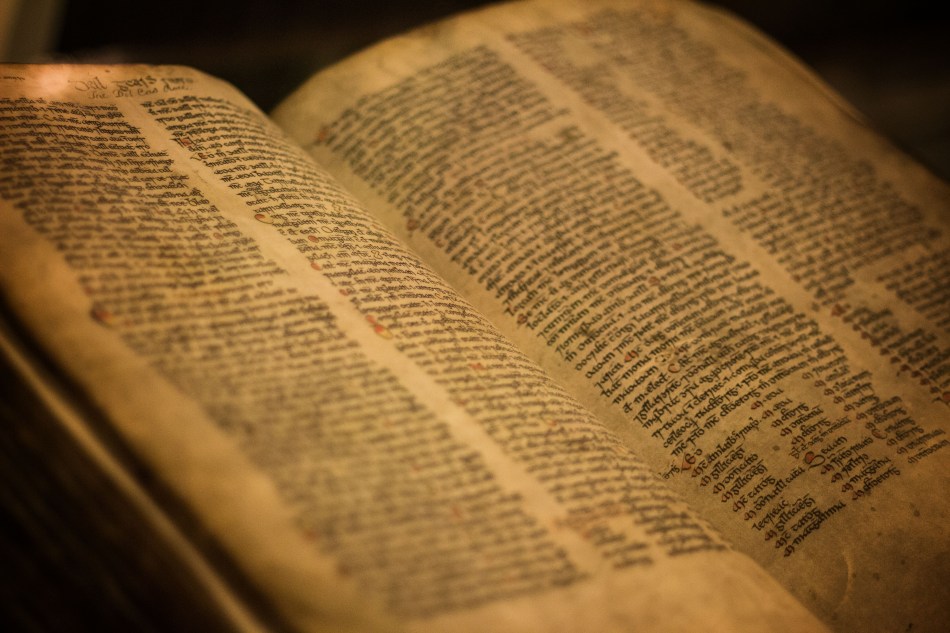

It’s generally understood that the loss of innumerable Medieval manuscripts during the Scandinavian, Norman-British and Anglo-British invasions of the Gaelic nations of north-western Europe has greatly impaired our understanding of the early histories of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man. Important narrative compendiums such as the oft mentioned Cion Droma Sneachta, the “Booklet of Droim Sneachta”, are almost certainly lost and beyond recovery. However those rare sources that have survived to the present day do provide an invaluable insight into the thinking and imagination of the early Gaelic peoples.

The most important of these manuscripts are the late 11th or early 12th century Leabhar na hÚidhre (or “Book of the Dun Cow”), the early 12th century Leabhar na Nuachongbhála (also known as the Leabhar Laighean or “Book of Leinster”), and the so-called Rawlinson Manuscript B 502 which may be or contain part of the missing 12th century Leabhar Gleanna Dá Loch (“Book of Glendalough”). Despite the relatively late periods given for these works most of the materials they contain pre-date their composition by hundreds of years and a few can be dated as far back as the 5th or 6th centuries.

Other crucial documents to have survived include a group of five manuscripts dating to the late 14th or early 15th centuries: the Leabhar Buidhe Lecain (“Yellow Book of Lecan”), the Leabhar Mór Leacain (“Great Book of Lecan”), the Leabhar Uí Mhaine (“Book of the Uí Mhaine”), the Leabhar Bhaile an Mhóta (“Book of Ballymote”) and the Leabhar Fhear Maí (“Book of Fermoy). Much later 17th century works such as Seathrún Céitinn’s Foras Feasa ar Éirinn (“Foundation of Knowledge on Ireland”) and the collaborative Annála na gCeithre Máistrí (“Annals of the Four Masters”) are also important, particularly as these later compilers and writers may have had access to manuscript sources that have since disappeared.

When using these materials it is always necessary to question the impact of the circumstances in which they were created. The vast majority of the manuscripts were produced by monastic scribes who may well have been torn between their desire to record the pre-Christian traditions of Ireland and Scotland on the one hand and their religious hostility to those self-same non-Christian traditions on the other. As a result most of the manuscript sources form part of a literary movement to establish a history for the Gaelic peoples that could bear comparison with that of other Christianised peoples in Europe (as found for instance in the works of Nennius, Geoffrey of Monmouth and the British monastic schools). This movement, taking root in the monasteries of Medieval Ireland, slowly developed a new body of historical and genealogical works for newly Christianised societies based upon indigenous pre-Christian oral beliefs mixed with Biblical, ecclesiastical and Classical influences from across Europe and beyond.

The Cycles

Traditionally Irish and other Gaelic scribes divided their literary corpuses into two basic schemes, príomhscéalta or primary tales and foscéalta or secondary tales, almost certainly continuing native practice. These were then further divided into sub-classes based upon themed genres: cattle-raids, plundering, battles, wooings and others. However, from the 19th century onwards scholars have tended to divide what we call Irish, Scottish and Manx mythology into four distinct, if overlapping, legendary or literary cycles. These are: the Seanchas (the Mythological Cycle; though Seanchas can also be applied to the mythological tradition as a whole), the Rúaríocht (the Ulster or Red Branch Cycle), the Fiannaíocht (the Fenian or Ossianic Cycle) and the Scéalta na Rí (the Historical or Kings’ Cycle). Additionally there are also a number of texts and recorded folk tales that do not fit into any of these neat categories, though they often feature characters, places or events from one or more of the four great cycles.

Seanchas

The Seanchas is the least well preserved of the four categories. The most important sources for it are the Dinnseanchas or “Lore of (Prominent) Places” and the Leabhar Gabhála Éireann “Book of the Taking of Ireland” (commonly known as the Book of Conquests or Invasions). Other manuscripts help fill out the cycle with important tales such as the Aisling Aonghasa“Dream of Aonghas”, the Tochmharc Éadaoine “Wooing of Éadaoin” and independent accounts of the first and second battles of Má Tuireadh. Additionally the body of stories with the genre titles of Eachtraí “Adventures” and Iomramhaí “Voyages” have become very rich sources of mythic lore.

The Eachtraí essentially recount tales of visits to the Sí or Otherworld, originally the afterlife and abode of the gods in the indigenous tradition, usually by a hero or heroes, and would seem as a narrative style to be of very ancient origin. In fact they almost certainly continue a pre-Christian custom of storytelling albeit much adapted by the monastic scribes. The most famous (if historically late) legend is Oisín in Tír na nÓg “Oisín in the Land of the Young” and belongs to the Fiannaíocht but several free-standing adventures survive including the Eachtra Choinla “Adventure of Conla”, the Eachtra Laoire “Adventure of Laoire”, and the important Eachtra Bhrain mac Feabhail “Adventure of Bran son of Feabhal”, all of which date from very early periods.

The Iomramhaí on the other hand are tales of sea journeys to the Otherworld (whether explicitly so or in disguise). These probably grew from the influence of Classical literature in the Christian period combined with the same native elements that informed the Eachtraí. Of the many iomramhaí mentioned in the manuscripts only three survive: the Iomramh Mhaoil Dúin “ Voyage of Maol Dúin”, the Iomramh Uí Chorra “Voyage of the Uí Chorra”, and the Iomramh Sneadhghais agus Mac Riaghla “Voyage of Sneadhghas and Mac Riaghla”. The Voyage of Maol Dúin is the forerunner of the later Navigatio Sancti Brendani Abbatis “Voyage of Saint Breannán the Abbot”, an important Christian tale that garnered much popularity in continental Europe (the title is commonly translated from Latin as the voyage of Saint Brendan). It should also be noted that the Otherworldly adventures of Bran son of Feabhal are sometimes known as the Iomramh Bhrain mac Feabhail.

The Dinnsheanchas

The Dinnsheanchas is the great topographical compendium of early Ireland explaining the names and stories of significant places throughout the island in a sequence of poems. It is probably the major surviving source of Irish bardic verse with nearly 200 works of poetry containing important information on characters and stories from throughout the literary tradition (some of which have yet to be adequately translated). The verses are accompanied by an incomplete commentary now known as the Prose Dinnsheanchas which contains much valuable lore (the main poetical body is known as the Metrical Dinnsheanchas to modern scholars).

Leabhar Gabhála Éireann

The Leabhar Gabhála Éireann itself is a synthetic-history of Ireland, Scotland and the Isle of Man began in the monastic schools of the 6th and 7th centuries and reaching its most developed form in the 12th century. It subsumed the pre-Christian oral beliefs of the Gaelic peoples into the body of the Roman, Greek and Judaeo-Christian myths accepted by the early Christian Church in Europe to give the Irish, Scots and Manx a suitable framework in which could be placed their histories, genealogies, poetry and literature. As a result the indigenous traditions of the pre-Christian Gaels pervade the compendium albeit largely in a hidden or debased form. It has survived in several broadly similar versions or redactions dating between the 11th and 17th centuries, evolving from mainly verse texts to a largely prose one. The details below are drawn from the earliest accounts found in the Leabhar na Nuachongbhála (more commonly, the Leabhar Laighean).

The Ceasaraigh

Under the LGÉ schema the Church-approved ancestry of the Irish was of course traced back to the Biblical Ádhamh “Adam”. Through his line came several groups of settlers to the island of Ireland (and latterly Scotland and Mann). The first of these were the Ceasaraigh or the followers of Ceasair, daughter of Bioth son of Naoi (“Noah”) and his wife Biorean, who were comprised of fifty women and three men (Bioth, Fionntán and Ladhra). Their story begins with Naoi advising them to flee the predicted Deluge by going to the western edge of the world and a land which might lie beyond its reach (later redactions have Ceasair’s father Bioth being refused a place in the Old Testament ark by Naoi and Ceasair advising him to worship an “idol” which instructed them to go to sea in a ship of their own construction). After setting sail in three ships they reached Ireland forty days before the Flood though two of the ships foundered on the coast. The surviving women were divided amongst the men, Fionntán (son of Bóchra or Bóchna “Ocean”) taking Ceasair in his share.

However the flood soon drowned all of the company with the exception of Fionntán. Later versions have Bioth and Ladhra dying of causes unknown before the flood and Fionntán fleeing the widowed women for some unexplained reason. In this scenario Ceasair die’s of a broken heart on the eve of the Biblical deluge which killed everyone except for Fionntán who was transformed into a salmon hidden in a cave on an Irish mountain. This expanded version then returns to the oldest text which has him living on in various guises when the waters receded, from salmon to eagle, a hawk to a reborn man, retaining the knowledge of all he had seen and done in the previous 5,500 years.

An alternative (possibly earlier) version of the story gives the name of the leader of the fifty women as Banbha and claims that they came to Ireland 240 years before the flood but died of plague after just 40 years in the country.

The Parthalánaigh

The Ceasaraigh were followed after the retreating of the flood waters by the Parthalánaigh “People of Parthalán”, under their leader Parthalán son of Seara, another descendant of Naoi (Parthalán is derived from the Latin “Bartholomaeus”, a name which featured in several early and influential continental Christian histories). They had travelled from Sicily to Greece, then on to Anatolia, an unidentified “Gothia” and thence to Spain arriving in Ireland some 300 or 312 years after the Deluge. In the more developed recensions they consisted of a thousand individuals including Parthalán’s wife Dealghnadh, their three sons and lords Sláine, Ruairí and Laighlinne, and their wives Nearbha, Ciochbha and Cearbhnadh.

When the Parthalánaigh arrived in Ireland there were only three lakes, nine rivers and one open plain in the country. However he and his people cleared four more plains of their vegetation and seven more lakes erupted from the ground. Some ten years after arriving the Parthalánaigh defeated the monstrous one-legged, one-armed Fomhóriagh led by Ciochal Grigenchosach son of Goll who perished along with all of his people in the first battle fought on the island. Their origin is never stated though it may be presumed that they must have also come to Ireland from elsewhere, presumably after the Parthalánaigh.

It was four sons of Parthalán, Ear, Oirbha, Fearghna and Fearan, who divided Ireland for the first time creating four territorial divisions. His people also introduced the first cattle (four bulls), dwellings, an ale-house, druids, scholars, champions, ploughmen and legal sureties (laws). Later Parthalán and his followers (now five thousand men and four thousand women) died of a plague in a single week leaving the island denuded of any inhabitants except for one man, Tuan son of Starn son of Seara (later texts call him Tuan son of Caireall), who underwent a series of transformations in animal and human form in an evident repetition of the story of Fionntán of the Ceasaraigh.

The Clann Neimheidh

The third settlement in Ireland, by the Clann Neimheidh “Family of Neimheadh”, came thirty years after the loss of the Parthalánaigh and lasted for many decades. Neimheadh (“Sacred One”), a son of Aghnamhan, was another descendant of Naoi and distantly related to Parthalán through the latter’s brother Taidh. He set out from an area near the Caspian Sea (“the Greeks of Scythia”) with his four sons, Starn, Iarbhaneal, Annind and Fearghas Leathdhearg, and their followers in a fleet of 44 ships though only one reached its destination after a year and a half of sailing. In Ireland Neimheadh led his people in four great victories over the Fomhóraigh, the most important being the first against their leaders Gann and Seanghann both of whom were slain (though it is not stated explicitly in any manuscripts it seems likely that the Fomhóraigh attacked after the Clann Neimheidh took control of the country). During his lifetime he cleared twelve plains of their forests and four lakes erupted from the soil. After that he died during a plague (in later redactions it occurred nine years after he arrived in the country and nine thousand of his followers died with him in another repetitious theme).

The surviving Clann Neimheidh lived under the oppression of the Fomhóraigh leaders Morc son of Daola and Conann son of Faobhar paying a heavy tribute of two thirds of their children, wheat and milk each year at Samhain (the great autumn-winter festival) until they rose in rebellion against their overlords. Led by Seamhal son of Iarbhaneal, Earghlan son of Beoan son of Starn and Fearghas Leathdhearg they assaulted Túr Chonainn or Conann’s Tower, the island stronghold of the Fomhóraigh and home of their fleet. With thirty thousand attacking by land and thirty thousand by sea they captured the tower and slew Conann but soon afterwards Morc arrived with the crews of sixty ships. A mutually destructive battle took place even as the incoming tide overwhelmed the combatants so that only one boatload of thirty men from the Clann Neimheidh escaped the catastrophe.

Of these survivors Beothach son of Iarbhoneal son of Neimheadh died of plague in Ireland, his ten wives living for another twenty-three years after him. Iabhath and his son Bathh went into the north of the world while Mathach, Earghlan and Iarthach, the three sons of Beoan, went to Dobhar and Iardhobhar in the north of the island of Britain (or Scotland). Finally Seameon son of Iardhan fled southward to An Ghréig (Greece) where his descendants flourished. It was from these groups of exiles that the next two waves of settlers descended.

The Fir Bholg

Those who went to An Ghréig became the ancestors of a people known as the Fir Bholg “Men (People) of Bolg” (a race which in fact also contained two other sub-groups known as the Gailíon and the Fir Dhomhnann “Men of Domhnainn”). Seameon’s descendants, numbering in the thousands, lived in slavery for many years under Greek servitude until eventually they rose up and migrated back to Ireland under their lords Gann, Geanann, Ruadhraighe, Seanghann and Sláine the sons of Daola son of Loth, some 230 years after the death of Neimheadh. They had nine kings in Ireland, the last being Eochaidh son of Earc.

The Tuatha Dé Danann

Those who went northward became the Tuatha Dé Danann “Peoples of the Goddess *Dana”. Not much is known of the Tuatha Dé prior to their invasion of Ireland other than that they came from four cities in the Insí Tuaisceartach or northern islands of the world where they acquired their knowledge and magical attributes. These cities also contained four great talismans which they brought with them. From Fálias came the Lia Fáil “Stone of Fál” on which their kings were proclaimed. From Gorias came the Claíomh Solais “Sword of Light” wielded by their king Nuadha. From Muirias came the cauldron of the Daghdha, and from Fionnias came the Sleá Lúgha or “Spear of Lúgh” (also called the Sleá Bua “Spear of Victory”).

The earliest accounts state that the Tuatha Dé arrived in Ireland in dark clouds on a mountain in the west of the country, blocking out the sun for three days and three nights. Later redactions have them arriving in ships which they burned in order to prevent themselves from being tempted into retreating or returning home, while a third legend conflates both stories the dark clouds coming from the burning of their vessels. They conquered the Fir Bolg after defeating them in the First Battle of Má Tuireadh granting the survivors the westernmost province of Connacht and sundry islands to dwell in.

However, during the battle their king Nuadha (who reigned for seven years before they reached Ireland) lost his hand or arm, which was cleaved from his shoulder during combat with the Fir Bolg champion Sreang. Since he was no longer physically perfect, a requirement of sovereignty, he was replaced by Breas (or Eochaidh Breas) son of Éiri of the Tuatha Dé and Ealadha of the Fomhóraigh, a race who now make their reappearance living in a territory or islands to the north or north-east of Ireland (sometimes called Lochlainn and of course in the same mythical region from which the Tuatha Dé came). However the reign of Breas was a tyrannical one and the Tuatha Dé were heavily oppressed by the Fomhóraigh (as were their Clanna Neimheidh ancestors before them, clearly an important theme).

Nuadha eventually had his hand or arm replaced by a silver one (made by Dian Ceacht the craftsman) gaining the sobriquet Lámhairgead “Silverarm” and took back the throne after the Tuatha Dé Danann rose up and exiled Breas for his seven-year tyranny. Breas fled to his father and the Tuatha Dé soon faced an invasion from their ancestral enemies, the Fomhóraigh, led by their king Inneach along with Breas, Ealadha, Teathra and their champion Balar (who dwelt in a northern island fortress called Túr Bhalair or “Tower of Balar”). However just before the battle the leadership of the Tuatha Dé was granted to a youthful and somewhat mysterious champion Lúgh Lámhfháda “Lúgh of the Long Arm”. Lúgh was the son of Eithne daughter of Balar and Cian (or Scál Bhalbh) the son of Dian Ceacht. He was also the foster-son of Tailte daughter of Má Mhór of Spain and wife of Eochaidh son of Earc. In his character was united the Tuatha Dé Danann, Fomhóraigh and Fir Bolg.

At the Second Battle of Má Tuireadh the Tuatha Dé lost Nuadha who was slain by Balar and Oghma who was slain by Inneach. However Lúgh slew his maternal grandfather with a stone from his sling – a common early Irish weapon – and his people gained victory. He then reigned as the king of the Tuatha Dé until followed in succession by the Daghdha (Eochaidh Ollathair son of Ealadha), Dealbhaodh, Fiacha and finally the joint-kingship of the Daghada’s three grandsons: Mac Cuill, Mac Gréine and Mac Ceacht the sons of Cearmaidh.

The Clann Mhíle

After all of the above the last invaders were the Clann Mhíle or “Family of Míl” commonly known in English by their anglicised name: the Mílesians. They were in effect the Irish people (hence the Irish are known variously as the Clann Mhíle, the Féine, the Gaeil and the Éireannaigh). They were the followers of Míl na Spáinne (“Míl of Spain”) who never made it to Ireland himself, instead dying in Iberia. His brothers and sons led the Clann Mhíle into Ireland arriving from their ancestral home in An Spáinn or Spain (encountering along the way a seemingly lifeless tower set in the middle of the sea) and defeated the Tuatha Dé Danann at the Battle of Tailte. After a short resistance from the latter both sides agreed a truce that led to the island of Ireland being divided between the two: the Clann Mhíle took the part above the ground while the Tuatha Dé Danann were given the part under the ground. The Tuatha Dé Danann were then led into the Sí by the Daghdha (that is the Otherworld and its many hidden residences). They consequently became frequent background figures in Irish, Scottish and Manx mythological or folkloric tales, the Aos Sí of “People of the Otherworld” who interacted with the peoples in the “world above”.

Éiremhan, a son of Míl na Spáinne, received the rule of the northern half of Ireland, and Ebher Fionn, one of the lords of the Clanna Mhíle, was granted the rule of the southern half the dividing line being the Eiscir Riada, the great line of low hills which ran from Áth Cliath (Dublin) to Gaillimh (Galway). Some time later both parts went to war, with Ebher Fionn being defeated and slain in battle. Éiremhan took the rule of all the territory becoming the first “Irish” king of Ireland. Many, many centuries later Ireland was again divided along the same territorial line into Leath Choinn, ruled by Conn Céadchathach in the north, and Leath Mhogha, ruled by Mogh Nuadhad in the south but that lies within the semi-historical period of the Kings’ Cycle.

Afterwords

As is apparent from reading the above the legends around the Leabhar Gabhála Éireann represent an extraordinarily complex mix of Celtic, Christian and Classical mythology and history as well as new literary speculations on behalf of its authors. That this did not happen in one place or period but was rather the product of many centuries of development make it all the more labyrinthine in interpretation. Certainly some reoccurring themes are obvious: territorial invasions, the shaping of landscapes though the formation of plains and lakes, plagues, island- or sea-towers, battles, floods by sea or tide, and many more. Equally many names are repetitious, applied to multiple characters some of whom are clearly clones of each other. It is little wonder that modern scholars have spent the last two hundred years trying to tease out all this in an attempt to arrive at some original form. Or that such a width of time, geography and story continues to attract writers, poets and artists.

© An Sionnach Fionn

[Rough First Draft 07.12.2011]

Online Sources For The Above Articles:

- Warriors, Words, and Wood: Oral and Literary Wisdom in the Exploits of Irish Mythological Warriors by Phillip A. Bernhardt-House

- Irish Perceptions of the Cosmos by Liam Mac Mathúna

- Water Imagery in Early Irish by Kay Muhr

- The Bluest-Greyest-Greenest Eye: Colours of Martyrdom and Colours of Winds as Iconographic Landscape by Alfred K. Siewers

- Fate in Early Irish Texts by Jacqueline Borsje

- Druids, Deer and “Words of Power”: Coming to Terms with Evil in Medieval Ireland by Jacqueline Borsje

- Geis, Prophecy, Omen and Oath by T. M. Charles-Edwards

- Geis, a literary motif in early Irish literature by Qiu Fangzhe

- Honour-bound: The Social Context of Early Irish Heroic Geis by Philip O’Leary

- Space and Time in Irish Folk Rituals and Tradition by Lijing Peng and Qiu Fangzhe

- The Use of Prophecy in the Irish Tales of the Heroic Cycle by Caroline Francis Richardson

- Early Irish Taboos as Traditional Communication: A Cognitive Approach by Tom Sjöblom

- Monotheistic to a Certain Extent: The ‘Good Neighbours’ of God in Ireland by Jacqueline Borsje

- The ‘Terror of the Night’ and the Morrígain: Shifting Faces of the Supernatural by Jacqueline Borsje

- Brigid: Goddess, Saint, ‘Holy Woman’, and Bone of Contention by C.M. Cusack

- War-goddesses, furies and scald crows: The use of the word badb in early Irish literature by Kim Heijda

- The Enchanted Islands: A Comparison of Mythological Traditions from Ireland and Iceland by Katarzyna Herd

- The Early Irish Fairies and Fairyland by Norreys Jephson O’ Conor

- The Washer at the Ford by Gertrude Schoepperle

- Milk Symbolism in the ‘Bethu Brigte’ by Thomas Torma

- Conn Cétchathach and the Image of Ideal Kingship in Early Medieval Ireland by Grigory Bondarenko

- King in Exile in Airne Fíngein (Fíngen’s Vigil): Power and Pursuit in Early Irish Literature by Grigory Bondarenko

- Sacral Elements of Irish Kingship by Daniel Bray

- Kingship in Early Ireland by Charles Doherty

- The King as Judge in Early Ireland by Marilyn Gerriets

- The Saintly Madman: A Study of the Scholarly Reception History of Buile Suibhne by Alexandra Bergholm

- Fled Bricrenn and Tales of Terror by Jacqueline Borsje

- Supernatural Threats to Kings: Exploration of a Motif in the Ulster Cycle and in Other Medieval Irish Tales by Jacqueline Borsje

- Human Sacrifice in Medieval Irish Literature by Jacqueline Borsje

- Demonising the Enemy: A study of Congall Cáech by Jacqueline Borsje

- The Evil Eye’ in early Irish literature by Jacqueline Borsje and Fergus Kelly

- The Irish National Origin-Legend: Synthetic Pseudohistory by John Carey

- “Transmutations of Immortality in ‘The Lament of the Old Woman of Beare'” by John Carney

- Approaches to Religion and Mythology in Celtic Studies by Clodagh Downey

- ‘A Fenian Pastime’?: early Irish board games and their identification with chess by Timothy Harding

- Orality in Medieval Irish Narrative: An Overview by Joseph Falaky Nagy

- Oral Life and Literary Death in Medieval Irish Tradition by Joseph Falaky Nagy

- Satirical Narrative in Early Irish Literature by Ailís Ní Mhaoldomhnaigh

- Lia Fáil: Fact and Fiction in the Tradition by Tomás Ó Broin

- Irish Myths and Legends by Tomás Ó Cathasaigh

- ‘Nation’ Consciousness in Early Medieval Ireland by Miho Tanaka

- Bás inEirinn: Cultural Constructions of Death in Ireland by Lawrence Taylor

- Ritual and myths between Ireland and Galicia. The Irish Milesian myth in the Leabhar Gabhála Éireann: Over the Ninth Wave. Origins, contacts and literary evidence by Monica Vazquez

- Continuity, Cult and Contest by John Waddell

- Cú Roí and Svyatogor: A Study in Chthonic by Grigory Bondarenko

- Autochthons and Otherworlds in Celtic and Slavic by Grigory Bondarenko

- The ‘Terror of the Night’ and the Morrígain: Shifting Faces of the Supernatural by Jacqueline Borsje

- ‘The Otherworld in Irish Tradition,’ by John Carey

- The Location of the Otherworld in Irish Tradition by John Carey

- Prophecy, Storytelling and the Otherworld in Togail Bruidne Da Derga by Ralph O’ Connor

- The Evil Eye’ in early Irish literature by Jacqueline Borsje and Fergus Kelly

- Rules and Legislation on Love Charms in Early Medieval Ireland by Jacqueline Borsje

- Marriage in Early Ireland by Donnchadh Ó Corráin

- The Human Head in Insular Pagan Celtic Religion by Anne Ross

- Gods in the Hood by Angelique Gulermovich Epstein

- The Names of the Dagda by Scott A Martin

- The Morrigan and Her Germano-Celtic Counterparts by Angelique Gulermovich Epstein

- The Meanings of Elf, and Elves, in Medieval England by Alaric Timothy Peter Hall

- Elves (Ashgate Encyclopaedia) by Alaric Timothy Peter Hall

- The Evolution of the Otherworld: Redefining the Celtic Gods for a Christian Society by Courtney L. Firman

- Warriors and Warfare – Ideal and Reality in Early Insular Texts by Brian Wallace

- Images of Warfare in Bardic Poetry by Katharine Simms

- Rí Éirenn, Rí Alban, Kingship and Identity in the Ninth and Tenth Centuries by Máire Herbert

- Aspects of Echtra Nerai by Mícheál Ó Flaithearta

- The Ancestry of Fénius Farsaid by John Carey

- CELT (Corpus of Electronic Texts) – published texts

- Mary Jones (Celtic Literature Collective) – translations

Printed Sources For The Above Articles:

- The Gaelic Finn Tradition by Sharon J. Arbuthnot and Geraldine Parsons

- An Introduction to Early Irish Literature by Muireann Ní Bhrolcháin

- Lebar Gabala: Recension I by John Carey

- The Irish National Origin-Legend: Synthetic Pseudohistory by John Carey

- Studies in Irish Literature and History by James Carney

- Ancient Irish Tales by Tom P. Cross and Clark Harris Slover

- Early Irish Literature by Myles Dillon

- Irish Sagas by Myles Dillon

- Cycle of the Kings by Myles Dillon

- Early Irish Myths and Sagas by Jeffrey Gantz

- The Celtic Heroic Age by John T Koch and John Carey (Editors)

- Landscapes of Cult and Kingship by Roseanne Schot, Conor Newman and Edel Bhreathnach (Editors)

- The Banshee: The Irish Death Messenger by Patricia Lysaght

- The Learned Tales of Medieval Ireland by Proinsias Mac Cana

- The Festival of Lughnasa: A Study of the Survival of the Celtic Festival of the Beginning of Harvest by Máire MacNeill

- Pagan Past and Christian Present in Early Irish Literature by Kim McCone

- The Wisdom of the Outlaw by Joseph Falaky Nagy

- Conversing With Angels and Ancients by Joseph Falaky Nagy

- From Kings to Warlords by Katharine Simms

- Gods and Heroes of the Celts by Marie-Louise Sjoestedt (trans Myles Dillon)

- The Year in Ireland by Kevin Danaher

- In Ireland Long Ago by Kevin Danaher

- Irish Customs and Beliefs by Kevin Danaher

- Cattle in Ancient Ireland by A. T. Lucas

- The Sacred Trees of Ireland by A. T. Lucas

- The Lore of Ireland: An Encyclopaedia of Myth, Legend and Romance by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin

- Irish Superstitions by Dáithí Ó hÓgáin

- Irish Folk Custom and Belief by Seán Ó Súillebháin

- Armagh and the Royal Centres in Early Medieval Ireland: Monuments, Cosmology and the Past by NB Aitchison

- Land of Women: Tales of Sex and Gender from Early Ireland by Lisa Bitel

- Irish Kings and High-Kings by John Francis Byrne

- Early Irish Kingship and Succession by Bart Jaski

- A Guide to Early Irish Law by Fergus Kelly

- Early Irish Farming by Fergus Kelly

- A Guide to Ogam by Damian McManus

- Ireland before the Normans by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín

- Early Medieval Ireland: 400-1200 by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín

- A New History of Ireland Volume I: Prehistoric and Early Ireland by Dáibhí Ó Cróinín (Editor)

- Early Ireland by Michael J O’ Kelly

- Cattle Lords & Clansmen by Nerys Patterson

- Sex and Marriage in Ancient Ireland by Patrick C Power

- Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe by H R Ellis Davidson

- The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe by Hilda Ellis Davidson

- Lady with a Mead Cup by Michael J Enright

- Celtic Mythology by Proinsias Mac Cana

0 comments on “Seanchas Agus Litríocht Na nGael”