The Battle of Pettigo and Belleek in the summer of 1922 was the largest military engagement between the Irish Republican Army and the British Occupation Forces in Ireland since the Easter Rising of 1916, and arguably the last significant action in the island nation’s War of Independence. Taking place from the 27th of May to the 8th of June the confrontation symbolised a final effort by revolutionary period republicans – already divided over a compromise peace deal with the United Kingdom – to contest the UK’s continued presence in the country. Within weeks of the encounter many Irish participants in the battle would find themselves on rival sides in the intra-nationalist Civil War of 1922-23.

The National Overview

Tuesday the 21st of January 1919 is often cited as the date on which Ireland’s four year War of Independence began. On that day nine volunteers or citizen-soldiers of the 3rd Tipperary Brigade of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) confronted two officers of the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC), the United Kingdom’s locally-recruited paramilitary police force, on a rain-swept road near Soloheadbeg quarry, County Tipperary. The early afternoon ambush, in pursuit of arms and explosives, quickly turned violent when the armed constables failed to surrender, both men dying in a hail of gunfire. Though the fatalities were unusual the encounter itself was not, clashes between the “rebels” and the “Crown forces” occurring intermittently since March of the previous year.

In truth what gave the event retrospective importance was its timing. On the same day as the attack representatives of Sinn Féin, the republican-nationalist party which had swept to an island-wide victory in the general election of December 1918, established Dáil Éireann or a republican parliament in the future capital city of Dublin. The Dáil gave form and substance to a revolutionary republic proclaimed three years earlier in the Easter Rising of 1916 and to the Irish people’s desire to regain their freedom from the colonial rule of the UK. Thus the incident at Soloheadbeg was recast as the “official” opening salvo in a popularly mandated insurrection against the British Empire.

For the next two-and-a-half years, the insurgent and counter-insurgent struggle between the several thousand volunteers of the IRA and the UK “garrison” on the island – the 57,000 members of the Imperial Armed Forces, the 14,200 officers of the regular RIC (including some 9,800 men recruited mainly from Britain and described variously in contemporary accounts as permanent, special, temporary or reserve constables, though they were popularly known as the “Black and Tans”), the 2,200 cadets of the Auxiliary Division of the RIC (the feared ADRIC or “Auxies”), some 1,100 men in the Dublin Metropolitan Police (DMP), the two dozen officers with the Belfast Harbour Police, the 32,000 militiamen of the Ulster Special Constabulary (the USC or “Specials”), and numerous individuals in various quasi-military groupings – shaped nearly all facets of contemporary Irish life. The insurrectionist republic, ratified by local and national plebiscite-elections in January and June 1920 and May 1921, gained an Aireacht or government under the presidency of Éamon de Valera, complete with ministerial departments, a civil service, police, courts, diplomats and, of course, an underground defence force. Meanwhile centuries of foreign authority, haphazardly erected through historic layers of law and officialdom, collapsed in the face of a popular revolt, withdrawing to the main urban centres, as well as to the unionist north-east of the country: a geographically transplanted facsimile of the medieval English Pale. In time, domestic and international pressure, coupled with a general war weariness, would lead to a bilateral ceasefire, the Irish-British Truce of July 11th 1921.

Nearly six months later, and in circumstances that remain controversial to the present day, prolonged negotiations between the representatives of the Dublin and London administrations culminated in the signing of a peace deal in the cabinet room of No. 10 Downing Street. Under the new “Treaty between Great Britain and Ireland” of December 6th the partition of the island into two separate jurisdictions, imposed by the British in 1920, would be formally recognised by the independence movement. A new, largely sovereign polity, the Irish Free State, would be established in the twenty-six counties of “Southern Ireland” while in the remaining six counties of “Northern Ireland” – the unionist-dominated north – there would be a semi-autonomous zone of the UK. This would result in one fifth of the territory of the island being left in British hands. The principal signees on behalf of the government of the Republic were Arthur Griffith, vice-president and secretary of state for foreign affairs, and Michael Collins, secretary of state for finance (who was also serving or had served as the adjutant general, director of organisation and director of intelligence for the Irish Republican Army). Their opposite numbers in the government of the United Kingdom were David Lloyd George, prime minister, and Winston Churchill, the secretary of state for the colonies.

The legitimacy of the treaty and the concessions it required split the independence movement and the country as a whole. Many critics argued that the negotiators had gone beyond the instructions given to them by their cabinet colleagues and president de Valera. Others pointed out that their actions violated the articles and spirit of Bunreacht Dála Éireann or the Dáil Constitution (adopted in January 1919) and the subsequent oath taken by all members of the government and defence forces to preserve it.

“I … do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I do not and shall not yield a voluntary support to any pretended Government, Authority, or Power within Ireland hostile and inimical thereto; and I do further swear (or affirm) that to the best of my knowledge and ability I will support and defend the Irish Republic, which is Dáil Éireann, against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; and that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion, so help me God.”

Though the proposed accords gained parliamentary approval in the Dáil on January 7th 1922, with a voting majority of just seven TDanna or deputies out of 121, irreconcilable camps quickly emerged on both sides. The so-called “anti-treaty” group were led by Éamon de Valera, now resigned from the presidency, while the breakaway “pro-treaty” faction were led by Michael Collins and Arthur Griffith.

On January 14th the “treatyite” members of Sinn Féin and the IRA, in line with the settlement reached in London, formed a transitional “Provisional Government” under the chairmanship of Collins (this administration remained in place until December of 1922). However many of those in the interim body retained their membership of the Aireacht. Collins was now the Chairman of the Provisional Government and the Minister of Finance in the Republican Government while Griffith later served as the Minister for External Affairs in the Provisional Government while also holding the office of the President of the Republic. Though some people were clearly in one administration or the other, a majority found themselves with a foot in both camps as the rival authorities remained entangled until the end of the year.

Meanwhile Dáil Éireann itself continued to function as the legislature of the Republic even as plans were laid for it to be subsumed into a treaty-required “Provisional Parliament” (the latter destined to become the assembly of the Free State). This process was made more complex by Britain’s insistence that the largely theoretical “House of Commons of Southern Ireland“, the UK-enacted home rule parliament for the twenty-six counties, was the only lawful legislature in the south until the Provisional Parliament took its place. In British eyes the Dáil remained an illegal entity, the chief cause of an armed rebellion against the authority of the crown. Yet for most of 1921 and 1922 London found it necessary to deal with its political and military representatives on an almost daily basis.

In some ways the chaos created through the competing claims of legitimacy on the island suited the needs of the pro-agreement Irish and British sides, aptly reflecting the creative ambiguities and outright deceptions both groups found necessary in order to bring about a compromise settlement that neither truly favoured. Given a constitutional black hole where anything seemed permissible the “Provisionals” readily exploited their lack of democratic or legal oversight during the early months of 1921 to silence or push aside their critics.

Unsurprisingly the confusion of allegiances created by the Downing Street accords were also reflected in the Republic’s defence forces, the Irish Republican Army, which had been on a general ceasefire in the greater part of the country since July 1921. In the first quarter of 1922 the treaty was put to individual votes across the army and an overwhelming majority expressed opposition to what they saw as the unconstitutional “usurpation” of the 1916 republic with a self-ruling “vassal” of the British Empire. Ironically, given future events, aside from the isolated Dublin Brigade and a few other units, the greatest support for the proposed deal came from the war-weary volunteers of the army’s five divisions in Ulster where the 1921 truce had failed to take hold. Promises from the leadership of the pro-agreement camp, particularly Michael Collins, had convinced many of these men and women that the settlement was simply a ploy which would lead in time to the liberation of the north-east. What they demanded was not debates but weapons to defend their embattled communities. As a result of the split the Irish and UK press began to describe the units loyal to the Dáil Constitution as the “Anti-Treaty IRA” while the minority favouring the accords with Britain were characterised as the “Pro-Treaty IRA“. (A third, loosely organised body also existed: the “Neutral IRA“. This eventually took the republican position or simply quit the revolution altogether).

In January of 1922 the Provisional Government sought the loyalty of pro-agreement military units by reorganising them as the Irish National Army (INA) with Michael Collins as their new commander-in-chief from June onward. The core of this force was the IRA’s elite Dublin Guard, a previous amalgamation of the Intelligence Unit or “Squad” attached to Collins’ GHQ spy department in the capital and the Dublin Brigade’s Active Service Unit. It was to be joined in February by the seventy-strong Belfast City Guard, also made up of pro-treaty volunteers. While this controversial policy eventually gifted the political and military leadership of the Provisionals to one man, supported by Griffith and his metropolitan colleagues, it also facilitated the supply of munitions and equipment from the UK to a force directly under the control of Sinn Féin’s breakaway faction (the British expected this force to suppress domestic opposition in Ireland to the treaty should it be required). One of the first signs of this new relationship was the adoption of British infantry uniforms, dyed a dark green, by the former guerrillas.

However these changes were unpopular with many pro-deal volunteers, some older veterans refusing to describe themselves as anything but the “IRA” (later clarified as the “official IRA” or the “regular IRA“). For a few of these revolutionary fighters the new military title was rather too close to that of the old Irish National Volunteers, the armed wing of the Irish Parliamentary Party, former nationalist rivals of the independence movement. Furthermore since the Provisionals claimed authority over all parts of the defence forces the INA continued to refer to itself as the IRA in most of its official pronouncements and statements. It wasn’t until the autumn of 1922 that the Provisionals’ military bulletin, An tÓglach, ceased to be published in the name of the Irish Republican Army; from mid-September onwards it was issued simply by “the Army“.

In reality, putting aside all the grandiose titles, the INA began as a minor affair, with volunteers outside the capital acting as a near-unified force for several months after the signing of the Downing Street agreement. This ensured that the two competing chains of command, commonly known as the “Army Executive” (Anti-Treaty) and the “Army GHQ” (Pro-Treaty), would be very public in their support for the optimistically conceived “Army Re-unification Committee“. Indeed the GHQ Staff informally classed units as “regular” (or “the Regulars” and nominally pro-agreement) and “irregular” (or “the Irregulars” and nominally anti-agreement or neutral) until 1923. It was not until the outbreak of open warfare between the rival factions, and the mass recruitment of Irish-born, former British army soldiers and RIC officers into the ranks of the Provisionals, that the ties of comradeship were to be severed beyond all hope of recovery.

The North-East

Well away from the splits created in the independence movement by the 1921 Treaty, the governments in London and Stormont – the seat of the one-party unionist regime just outside Belfast – were busy securing the survival of the historic British colony on the island of Ireland; albeit now reduced to the six north-eastern counties of Derry, Tyrone, Fermanagh, Armagh, Down and Antrim: in other words, “Northern Ireland”. By the spring of 1922 the maintenance of this separatist zone and the disputed border around it required the deployment of some 50,000 soldiers, police officers and militiamen, the latter in the form of the locally recruited Ulster Special Constabulary. This organisation, known as the USC or more colloquially “the Specials“, was established by the UK authorities in 1920 using elements of the Ulster Volunteer Force, a pre-WWI pro-British terrorist grouping, to supplement the work of the RIC in the north of the island, eventually becoming an auxiliary police militia. However the USC had little regard for the views of Downing Street or Westminster, answering instead to local unionist leaders, its sectarian nature quickly exacerbating the effects of the war across the province of Ulster and beyond. Within two years of its creation a despairing Lloyd George, who had initially agreed with unionist demands for its establishment, was comparing the force to the fascist gangs of Benito Mussolini in Italy. The aptness of that analogy was to become more apparent in the months and years ahead.

Under Sir James Craig, the first “prime minster” in June of 1921 (a former British army officer, Orangeman and co-founder of the UVF in 1913), the Stormont administration instigated or at least facilitated a campaign of violence known to history as the “Northern Pogroms“: that is the ethnic cleansing of several classes of perceived undesirables – Roman Catholics, Jews, atheists, socialists, and even trade unionists – from what was to become a deeply conservative, quasi-theocratic state. Or as Craig would later put it:

“All I boast of is that we are a Protestant Parliament and a Protestant State.”

The prime culprits for the mayhem were the Specials, and by March of 1922 the rival Dublin authorities were struggling to respond to the orgy of blood-letting which had engulfed the “North“, and which had worsened in the wake of the previous year’s truce. Nationalist enclaves across the region were under siege, leaving hundreds of people dead and wounded, while thousands more were fleeing southwards to refugee camps around the capital. The city of Belfast alone would witness the expulsion of 22,000 Roman Catholics and “disloyal” Protestants by the year’s end (the latter excoriated by unionist politicians and journalists as “rotten Prods“). To make matters worse many members of the ruling establishment in Britain privately defended the “Orange Terror” as a necessary evil to safeguard the future of the United Kingdom. This was certainly the opinion of men like Sir Henry Wilson, a former field marshal in the British army and Chief of the Imperial General Staff from 1918 to 1922. Born into the Anglo-Irish or Protestant “Ascendancy“, the colonial aristocracy in Ireland, Wilson had led the mutiny amongst the locally garrisoned UK armed forces against home rule for the island several years earlier in 1914, and by February of 1922 he was acting as a unionist MP and military adviser to the dictatorship in Stormont. His malign twenty-year influence upon Irish-British relations was to make him a high-profile target for retaliation, something that was to lead to catastrophic consequences for the whole country.

In the first half of 1922 the northern divisions of the Irish defence forces were mounting a fierce resistance to the carnage in the Six Counties but were losing volunteers and equipment at a crippling rate. Consequently one of the few things most opponents or advocates of the treaty could agree upon was the need to support their desperately depleted units in “North-East Ulster“, regardless of their position on the London settlement.

Before this, in January and February, the British Occupation Forces had begun their gradual retreat from the Twenty-Six Counties by concentrating the majority of their troops in Dublin, Cork and Kildare (a number of specialist units, such as the cavalry, armour and artillery, were ordered to withdraw from the region immediately, either to the north-east of the country or to elsewhere within the empire). The disbandment of the RIC, already denuded of personnel, began soon thereafter, many officers seeking a transfer to the Six Counties or the further colonies. As the UK installations were evacuated rival units of the Irish Republican Army took up residence in the barracks and camps, the former authorities surrendering them to whichever faction arrived first (the exceptions to this were high-profile places like the capital’s Beggars Bush Barracks – which became the INA HQ on January 31st – or the sprawling Curragh Camp in Kildare, handed over to the pro-treaty forces on May 16th). As a part of the process of retreat the British began to donate several tonnes of war materials to the regular INA, almost all of it from the stockpiles of weapons and equipment belonging to their withdrawing forces.

In a daring scheme senior Pro-Treaty commanders arranged with their Anti-Treaty counterparts for a portion of these munitions, principally rifles and handguns, to be covertly transferred to anti-agreement units of the army in Munster and Connacht. These units in turn dispatched their existing weapons, in some cases dating back to 1913, to the beleaguered divisions of the defence forces in the north (where a narrow majority of volunteers were aligned with the INA). Ironically of course this meant that the British Empire was unknowingly rearming the very insurgents who were most opposed to its presence in Ireland.

For those wishing to foster unity in the IRA this covert co-operation offered a potential solution to the growing split: renewing the war of independence in two-thirds of Ulster to forestall internecine conflict nationally. Downplaying the growing incidents of violence between opposing units of the army, in the early summer of 1922 many optimists believed that enmity to the UK’s continued presence in the country would supersede any disagreements over the nation’s constitutional future. Even in the Twenty-Six Counties the breakdown in military discipline caused by the emergence of the Collins-Griffith faction had largely manifested itself through attacks on the remaining enemy forces, and not just by anti-treaty volunteers. As recently as April the 28th four British intelligence agents had been arrested by the IRA in Macroom, County Cork, and executed at nearby Kilgobnet.

(Three of the men, lieutenants Ronald A Hendy, George R A Dove and Kenneth R Henderson, were notorious war criminals associated with the British practice of torturing prisoners by dragging them behind moving vehicles until their bodies were mutilated or dismembered. Two were also suspected of involvement in the death of an elderly local woman during a house-raid the previous year. At the time of their executions all three were under the orders of the brutally incompetent boss of the operations and intelligence section of the British 17th Infantry Brigade in the province of Munster, Major Bernard Law Montgomery. He, of course, later gained fame as Field Marshal Montgomery of Alamein.)

Eventually concrete plans were laid between Michael Collins and General Liam Lynch, chief-of-staff with the Army Executive wing of the defence forces and one of the ablest field commanders of the entire period, to launch an operation known variously as the “Northern Offensive” or the “May Rising“. Intended to collapse the Stormont dictatorship and harry the UK into renegotiating the more objectionable aspects of the treaty the first attacks by northern-based units against the British Occupation Forces began on the night of Friday the 19th of May, 1922. Unfortunately a lack of coordination, confused orders, and contrary actions by volunteers serving with three army divisions under the influence of the Provisionals meant that the campaign quickly faltered. In time events across the rest of Ireland were to take a far different and more tragic course than those hoped for by the architects of the joint-offensive.

The Triangle

During the spring and early summer of 1922 contemporary press reports often referred to the triangular patch of land between the administrative counties of Donegal and Fermanagh as the “Pettigo and Belleek salient”. This was something of an exaggeration though one reflecting the language of the recent Great War and Britain’s view of the new “border” in Ireland as both an international boundary and the frontline in an ongoing struggle. In reality the salient was a sparsely populated area of wooded fields, small lakes, bogs and rugged terrain running along the northern shore of Lower Lough Erne, a forty-two kilometre elongated lake studded with dozens of islands, with the townlands of Pettigo to the north-east and Belleek some twenty-four kilometres to the south-west. Few serviceable roads existed in the region, limiting movement to a handful of well-known routes and a branch-line of the Great Northern Railway company which ran through the countryside from the eastern Bundoran Junction pass the villages of Irvinestown, Kesh, Pettigo, Castle Caldwell, and Belleek before going westward to Ballyshannon and the seaside resort of Bundoran in County Donegal.

The predominantly unionist village of Pettigo sat astride the Termon River, a narrow watercourse dividing the town in two before running south into Lough Erne. The majority of the population lived on the west bank, in Donegal, which also included the “diamond” or town square, the RIC barracks and the all-important train station. Steep hills dotted with woods and several small lakes dominated the countryside to the west and north, where much of the land was uncultivated. A short stone bridge connected the village to its eastern half in Fermanagh, a scatter of houses following the main road up a small slope until the route opened up into hedgerowed fields and copses. Before 1922 the village’s only real claim to fame stemmed from the regular cattle-markets held in the diamond and its association with the annual Lough Derg pilgrimages.

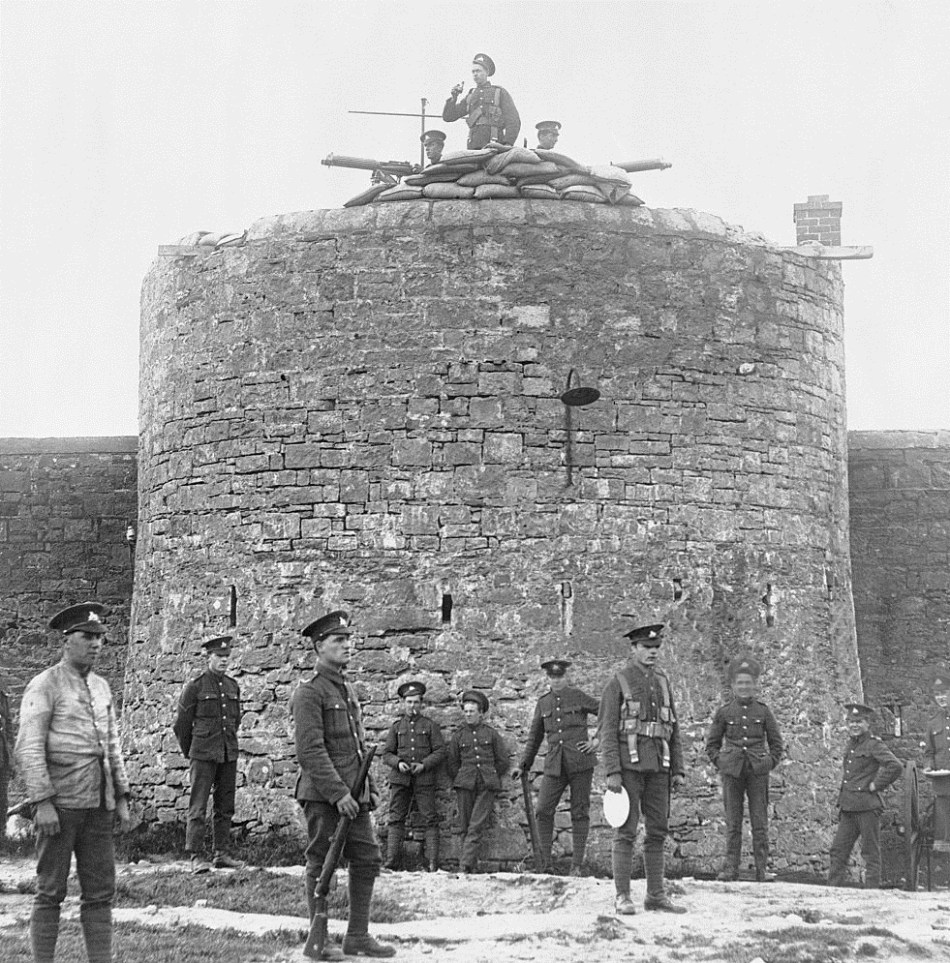

In contrast the mainly nationalist market-town of Belleek was built almost entirely on the eastern or Fermanagh side of the wide River Erne, the latter following a cascading course south-east into the northern waters of the lake. This is where most residences, retail outlets, a hotel, a pub and the famed pottery factory were to be found. A bridge of several arches crossed the river at an odd angle giving access to the west bank and Donegal, though the only notable feature here was the elevated Belleek Fort, an 18th century military building covering the river-crossing from atop a embankment and thick stone walls. It enjoyed good views over the neighbouring countryside and was to be the focus of much of the action in the forthcoming clashes.

At any other time in the history of Ireland these demographic characteristics would have been of little significance, crude indicators of colonial settlement and native displacement. However with the determination of the Stormont and London governments to impose a border around a separatist, pro-UK region of the island, suddenly such quirks of history and geography became the stuff of immediate war and terror.

In light of the planned offensive in the north-east the Pettigo-Belleek salient became a relatively secure forward-base for over one hundred volunteers from both sections of the divided defence forces, principally units attached to the anti-treaty 2nd Northern Division under Commandant-General Charles Daly (up to late April forces in the triangle had carried out a number of attacks on the British, including ambushing a USC patrol at Garrison in Fermanagh, though this was technically within the operational area of the treaty-split 3rd Western Division led by Commandant Liam Pilkington). In the aftermath of wide-scale arrests of republican activists in the north the salient also served as a safe haven for those being pursued by the UK authorities, including a large body of fatigued volunteers from Tyrone who were put to patrolling the countryside around Pettigo. The strategic importance of this otherwise rural backwater was reflected in the decision by Free State government to place “official” INA garrisons in the “southern” halves of the two divided villages in April of 1922, following the withdrawal of the RIC from the local barracks. Meanwhile IRA units, regardless of their official chain of command, were coordinating their activities in the area.

Unfortunately the Irish forces in the contested region were lightly armed at best, with a mixed variety of rifles, carbines and assorted handguns (not to mention some shotguns). The handful of available submachine guns and light machine guns were of limited use due to ammunition shortages. Hand grenades and landmines – whether conventional or improvised – remained scarce while artillery or mortars were non-existent. For transport civilian cars or captured military vehicles were employed, though even these were rare. In contrast the BOF were awash with standardised weapons and equipment, from armoured personnel carriers to aircraft. These differences were to be crucial in the coming days.

The First Assault on Belleek

Inevitably the presence of Irish forces in significant numbers along the “border” drew the ire of the unionist administration and community at large, leading the USC militias to launch a series of local pogroms against the nationalist populations in the counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone. Even Donegal and Cavan, part of Ulster but technically in the “South“, were subject to shootings and house-burnings. This was a reminder that the boundary-line between the two “states” was a political construct that had yet to be given concrete form. Resident populations ignored it and rival formations criss-crossed it at will. Indeed many RIC and USC men were from counties which were now in “Southern Ireland” and they had no intention of abandoning those ties. Consequently the British press was full of stories, albeit usually delayed or confused, charting the clashes between the opposing camps. After weeks of similar incidents the racketing tension culminated in an alleged occurrence at Pettigo, an event reported in dramatic terms by the local newspapers and repeated in the House of Commons by unionist MPs:

“LONDON, 31st May

LOYALISTS KIDNAPPED

Sinn Feiners kidnapped a number of loyalists at Pettigo Market on the Fermanagh border, whence the loyalists are fleeing, leaving everything behind.”

The victims were later claimed to be four USC officers, though no names were ever presented and no relatives came forth to seek their whereabouts. Whatever the truth about the “kidnapping”, it provided the Stormont authorities with the casus belli they required to prepare a full-scale assault upon the salient, though significantly against the more vulnerable town of Belleek rather than Pettigo. On Saturday the 27th of May a large group of USC men assembled just outside the disputed enclave under the leadership of Sir Basil Brooke, a former infantry captain, Orangeman and founder of a notorious paramilitary gang known as the “Fermanagh Vigilance“. Twenty-one years later Brooke would become a “prime minster of Northern Ireland” and the author of an infamous speech to the Orange Order where he declared:

“Many in this audience employ Catholics, but I have not one about my place. Catholics are out to destroy Ulster… If we in Ulster allow Roman Catholics to work on our farms we are traitors to Ulster… I would appeal to loyalists, therefore, wherever possible, to employ good Protestant lads and lassies…”

However in 1922 he was merely a ruthlessly sectarian leader of unionism in south-west Ulster determined to suppress any dissent from the “minority” community. Crossing westward over Lower Lough Erne from Roscor in County Fermanagh, with a flotilla of small boats towed by a hastily-armed pleasure-steamer known as “The Lady of the Lake”, Brooke landed near the townland of Leggs before marching his colleagues a short distance to the grounds of Magheramenagh (Magherameena) Castle, seven kilometres east of Belleek. Magheramenagh was a 19th century stately home built in the Tudor-Gothic style by the influential Johnston family, members of the Anglo-Irish aristocracy in the region. With the death in 1915 of the dynasty’s only son, Captain James Cecil Johnston, literally blown to pieces by a Turkish shell during the Allies’ disastrous Gallipoli campaign, the family emigrated to Britain (including Johnston’s widow and young daughter, the future novelist Myrtle Johnston).

By 1922 the sprawling house had become the dilapidated residence of Lorcán Ó Ciaráin, the recently appointed Roman Catholic parish priest in the district. Ó Ciaráin was an early member of Sinn Féin (indeed, he was credited with the naming of the party in 1905) and a pro-treaty confidant of Michael Collins, believing the promises from the Provisionals that the counties of Fermanagh and Tyrone would be included within the future Free State. His strategically placed home – with a train-stop inherited from its former aristocratic owners – was well suited to his role as a conduit for information between the independence movement in western Ulster and the entangled governments in Dublin. It also housed sessions of the local Dáil Court, which included the participation of the noted republican journalist Cahir Healy (despite being imprisoned without trial by the Stormont regime in May he was elected as a nationalist MP for Fermanagh and Tyrone that November). Unsurprisingly Ó Ciaráin was a unionist hate-figure and he was ejected from his dwelling at gunpoint, Brooke’s expedition proceeding to shoot at anyone who approached their encampment, including inquisitive neighbours. The militants were now holding a position that commanded the road and rail routes between Belleek and Pettigo.

Fearing a larger British invasion a small IRA force commandeered the strategically-sited Cliff House in Donegal, just to the north-west of Belleek, an impressive mansion on the banks of the River Erne owned by a major in the USC who was also a grand master of the Orange Order (this residence was destroyed in the construction of the Cliff Hydroelectric Power Station in 1946). Further coordination saw the withdrawal of the regular INA garrison from the Belleek Fort – known informally as the “Battery” – and its replacement with an Anti-Treaty contingent (in total there were no more than seventy volunteers on active service in the townland, the majority anti-agreement).

Shortly thereafter up to thirty IRA volunteers, following the railway line towards Pettigo, were intercepted by the Special Constables on the grounds of Magheramenagh demesne, a fierce fire-fight forcing the militiamen’s withdrawal. Pursued by the volunteers the USC abandoned the castle and conducted a chaotic boat-borne evacuation to Buck Island, a nearby islet with little in the way of natural cover at the mouth of Rossmore Bay. There they were reinforced by another one hundred paramilitary police, plus local doctors and nurses to attend their wounded colleagues. One unlikely figure to emerge from this rout was a Mrs. Laverton, owner and pilot of the steam-yacht “The Lady of the Lake” (renamed “HMS Pandora“), which was pressed into service during the rescue operations. She was hailed by the newspapers in Britain some days later as the pistol-wearing “Ulster Admiral“:

“LONDON, June 3rd

RELIEF OPERATIONS.

HEROIC LADY.

The most romantic figure in the Irish border struggle is ‘Admiral’ Mrs. Lavorlon, of ‘H.M.S. Pandora,’ the little steamer on Lough Erne,which, under fire, rescued the garrison of Ballynameena [i.e. Magheramenagh] Castle. Her achievement is the sensation of the North.

Smartly dressed in serge, she looks trim and business-like, with a revolver strapped to her waist, contrasting strangely with a becoming soft hat with a modest ‘Beatty’ tilt. She calmly related to an interviewer the story of the relief.

‘I ran in towards the castle,’ she said, ‘hove the ship to. The Specials aboard engaged the large bodies of Republicans whom we drove off with heavy losses. Then I noticed that, they opened the sluice-gates and there was danger of the Pandora stranding. I jumped into a row boat weighed the anchor, and pulled out into deep water.

‘I was constantly sniped at, but I had a rifle and I naturally fired back. I think I got several too.'”

In fact Laverton was forty-two year old Hazel Valerie West, the formidable daughter of a well-connected Ascendancy family from Wexford and the ex-wife of a former lieutenant-colonel in the British army, Herbert Curling Laverton OBE. Her paternal grandfather, Dublin-born William James West, had served as a Church of Ireland minister in Fermanagh and Tyrone for some time, and she and her husband of three years had moved to the relative solitude of Magheramenagh Castle as guests of the Johnston family in 1911 to aid his recovery from persistent ill-health. While the Lough Erne region was a popular hideaway for the wealthier scions of the settler nobility it seems that premature retirement from the imperial military did not suit Laverton and the outbreak of the Great War was his opportunity to abandon an itinerant, childless marriage for adventures overseas. By 1922 Hazel West was sojourning at the rather déclassé Imperial Hotel in Enniskillen, a year after her bitter divorce in London, where she owned the yacht that was to gain so much infamy in the coming weeks. Like most representatives of the colonial ruling class the middle-aged West had been unable to reconcile herself to the dramatic changes stemming from Sinn Féin’s victories in the elections of 1918, 1920 and 1921. One cannot help but wonder if the ownership of the Magheramenagh estate by the Catholic Church was one of those irreconcilable changes.

The Opening Attack on Pettigo and a Second Attack on Belleek

Early the next morning, Sunday the 29th, attention turned to the relatively quiet village of Pettigo, where the Irish forces numbered around sixty INA/Pro-Treaty volunteers and some thirty Anti-Treaty. The latter included Vice-Commandant Nicholas Smyth of the Fintona Battalion in the 2nd Northern Division. Alerted by night-time messengers from Belleek the Tyrone-born Smyth recounted that:

“Our officers decided to cut a trench across the road at Pettigo Bridge to prevent a rush through by enemy cars or tanks. While this work was in progress large numbers of enemy forces began to appear on the Fermanagh side of the border. As our working party was in grave danger should the enemy open fire, I was ordered to take a covering party of about 12 or 14 men to protect them. These men were armed with rifles. We took up positions overlooking the bridge. The enemy forces doubled and took up positions behind a hedge across from us. As the men making the trench were now in grave danger, being right in the line of fire from both sides, it was decided to withdraw the working party.

We didn’t wish to be the aggressors and I warned the men to withhold their fire and await orders. We must have been in that position for a couple of hours. The tension was great. The whole town had become very quiet and you could hear a pin drop when suddenly a shot ran out somewhere up the street. This was followed by three or four more single ones. This seemed to be a signal, because the whole place became alive with sound in a few minutes. Bullets were hitting the wall just over our heads and large lumps of lead were dropping on top of us. Our rifles were soon too hot to hold and the air was filled with the smoke and the smell of cordite. We had 100 rounds of ammunition each and most of it was gone before the enemy withdrew.”

After several hours of gunfire the USC men retreated eastward through the fields leaving wounded on both sides.

Meanwhile back in Belleek Commandant-General Joe Sweeney, head of the 1st Northern Division of the Pro-Treaty IRA/INA in west Ulster, who had been sent to report on the situation, narrowly escaped death when USC snipers targeted him in the village, curtailing his visit. Shortly thereafter a body of militiamen which had been dispatched to the enclave from the nearby town of Enniskillen in County Fermanagh, approached the area from the south-east in a convoy of three Crossley 20/25 Tenders (a type of unarmoured or lightly armoured military car) and two heavier Lancia Triota 1921 Armoured Trucks. Just outside Belleek, and actually inside Donegal, the convoy was ambushed by Irish units on a particularly narrow stretch of the road, the driver of the lead car dying in the initial volley, crashing into a ditch. Their way forward blocked, and subject to close fire from both flanks, the USC expedition panicked. Unable to turn around on the confined route they resorted to driving in reverse for nearly two kilometres eastward along the Lough Shore Road before abandoning their vehicles, dismounted men speeding on foot towards Lough Erne, where they came under further fire from the IRA sections now holding Magheramenagh Castle. The discarded equipment seized that day by the ambushers was to see service with the Anti-Treaty IRA in the coming months while the Pro-Treaty troops drove a captured Lancia Triota in triumph some fifty kilometres north to the INA’s Donegal HQ in Drumboe Castle, near Stranorlar.

The UK press was soon featuring telegraphed reports in its late editions:

“LONDON, 31st May

NORTH AND SOUTH CLASH.

Troop Concentrations Continue.

WARSHIPS LEAVE FOR IRELAND.

A sudden volley rang out on the Ulster frontier, westward of Fermanagh, on Sunday evening. A motor driver fell dead from his seat and long lines of Ulstermen and Southerners immediately blazed with fierce rifle fire. A serious battle developed wherein five Southerners were killed and several injured. One Ulsterman was killed. The motor driver was one of the Northern force carrying supplies to beleaguered garrisons whom the Southerners endeavoured to isolate. So far the police have kept the communicating lines intact.

Fierce fighting is in progress on the Fermanagh border and Pettigo a strong Orange centre, was occupied this morning by the Republicans, who joined the Free Staters, drove out the Protestants and occupied the houses. The rebels crossed the border and occupied the houses of leading Unionists. Refugees arriving, at Enniskillen report that a fight is progressing between Unionist forces and the rebels. Belleek was occupied by the Republicans this morning.

Bloodshed and outrage continue elsewhere. Isolated county houses and castles have been the scene of attacks by marauding armed men, and in many instances a heroic defence has been put up by the occupants and servants, who protracted the sieges and have beaten off the raiders.

There has been further fighting on the border at Clady, County Tyrone. The I.R.A. troops are concentrating in County Donegal.”

Further Attacks on the Pettigo Defenders

Later on Sunday evening a second convoy of USC men arrived in Pettigo, speeding eastward from their base at Clonelly House, Fermanagh, to secure a land-route via the townland of Lowery to the vulnerable militiamen on Buck Island in Lough Erne, who were under intermittent sniping from the Irish forces in Magheramenagh and Leggs. This sparked a further two-hour battle in and around the village as the British attempted to pass through it, eventually forcing the Special Constables to seek an alternative route to their trapped compatriots via a narrow sliver of marshland in the area of Toome, south-west of Pettigo, where the Waterfoot River and the Termon River entered Lough Erne. Unfortunately for the USC men by late Monday morning, the 29th of May, the IRA under Jim Scallon had successfully fortified themselves in this position – known locally as the Waterfoot – with a line of slit trenches and felled trees. The militia column proceeding on foot found its way blocked, leading to a quick fire-fight and even quicker retreat.

Sporadic clashes took place across the enclave throughout the following days, notably on Tuesday morning when another dawn-assault on Pettigo was thwarted. Commandant Smyth again witnessed some of the fighting at first-hand:

“…at daybreak a battle royal broke out around the village. From our positions we couldn’t see what was going on and I moved the men out along the railway line in order to be in position to cover the main road leading to the town. Some of the enemy were retreating down this road and our men opened fire on them. One of our men had a rifle fitted for firing grenades and he tried to get a few across the road. As far as I remember, they failed to hit the target. I found this experiment most interesting as I had never seen a rifle grenade fired before and I saw that at short range they could be very effective.”

The Deepening Crisis

By Monday afternoon the unionist dictatorship at Stormont was in a state of panic, believing the events in the south-west salient to be the herald of a full-scale “invasion” to retake the counties of Fermanagh, Tyrone and Derry. These fears were further stoked by regional newspapers which carried lurid reports of “Protestant” and “loyalist” families fleeing the fighting to seek safety in the eastern garrison-towns of Castlederg, Omagh and Enniskillen. Frantic telegrams and appeals to London were met with stalling from Downing Street, as Dublin prevaricated over its own involvement in the affair. Initial denials of INA troops operating in the area were soon switched to acceptance of their presence, though it was argued that they were acting purely defensively. In fact secrecy over the cooperation between Pro- and Anti-Treaty forces at the highest levels of the Provisional Government, particularly with the launch of the Northern Offensive, meant that no one in authority was exactly sure about the situation on the ground. Including the Provisionals’ leader, Michael Collins.

Meanwhile the UK prime minister, Lloyd George, was dismayed at the thoughts of being dragged into another war in Ireland, with the last one barely finished. He was also suspicious of unionist claims and the motivations of his own atavistic cabinet members over what he regarded as little more than a minor skirmish in the “swamps” of Fermanagh. In contrast to the relatively friendly relations he enjoyed with the Irish he found the unionists an embarrassment to the empire and its standing in the world. However the pressure to act, particularly from a bellicose Winston Churchill as the secretary of state for the colonies, forced his hand.

On Thursday the 1st of June, and under personal orders from Churchill who had staked his political reputation on the operation, a combined military and paramilitary force of regular British troops from the 18th Infantry Brigade, supported by drafted-in units of the RIC/RUC and Special Constabulary, approached the liberated townlands from the east in a long convoy of Crossley tenders, Lancia Triota trucks, Rolls-Royce armoured cars, and Medium Mark A Whippet tanks. Air-cover was provided by a newly dispatched squadron of Bristol F.2 Fighters from the Royal Air Force, based at the hastily upgraded Aldergrove aerodrome just outside Belfast, which were to carry out reconnaissance and artillery-spotting duties for the next two weeks.

The Final Assaults On Pettigo

Spreading out into the countryside the BOF troops took up positions around the village of Pettigo while smaller groups marched or drove north- and south-west. After a period of quiet a vanguard of twelve Crossleys were sent ahead, unaware that forward-posts in the vicinity had been ordered to hold their fire, leaving the initial defence to positions nearer the town. A devastating first volley seems to have caught the British attackers off-guard though they eventually replied with a hail of bullets from machine guns and rifles, concentrating on the IRA sections at Drumhariff Hill, immediately south-west of the village, and at the railway station. However the demoralising impact of the first contact and sustained casualties over the course of thirty minutes forced a chaotic withdrawal, cars and people colliding as they attempted to turn around on the narrow country road leading down to the river-crossing. Both sides were soon greeted with the sight of a police officer springing from a hiding place in the fields, flinging his weapon to one side, and chasing after his comrades, apparently generating much cheering from the defenders of Pettigo. That night and into Friday sniping between both sets of combatants took place in several flashpoint locations, the more experienced British Army marksmen often creeping to within 200 meters of the IRA lines before opening up.

By the morning of Saturday, June 3rd, the British had commandeered all the craft on Lower Lough Erne and assembled them at Portonode, just outside the eastern village of Kesh, where they were used to transport part of an infantry battalion of the Lincolnshire Regiment westward across the lake to the nearest tip of the elongated Boa Island. From there 200 soldiers marched north-west, carrying their boats to a point on the isle opposite the townland of Letter, just over three kilometres to the south-west of Pettigo, and west of the IRA strong-point of the Waterfoot. Under fire the British force crossed from Boa Island to the mainland in a battle that saw the reappearance of the pugnacious Hazel Valerie West:

“LONDON, June 7th

FIGHTING IN ULSTER.

REBELS OUTWITTED BY A WOMAN THEIR BOATS COMMANDEERED.

SUCCESSFUL REAR ATTACK.

The newspapers are giving prominence to Mrs. Laverton, the so-called “Woman Admiral” of the Lougherne [i.e. Lough Erne], who, aboard her yacht Pandora, commandeered a fleet of small boats for the transport of soldiers, who were thus able to take the Sinn Feiners in the rear. Some boats commandeered were in Sinn ‘Fein waters. The Sinn Feiners were chagrined, never believing that a woman would venture in bullet-swept waters. The “woman Admiral” wore a dainty pistol in her belt and on one occasion stalled off a Sinn Fein raid by mounting a brass telescope in the bow of her yacht and pretending it was a machine gun.”

In the meantime the rest of the battalion advanced from the village of Kesh to Lowery, immediately east of the Waterfoot, planning to link-up with the troops at Letter. However this required them to pass over the Irish-held isthmus. Throughout Saturday night the infantry battalion attacked less than thirty IRA men in the Waterfoot outposts on two fronts, in some of the most intense fighting seen in the confrontation. However the volunteers held their positions, relying on reinforcements from Pettigo who crept between the enemy lines to reach their isolated comrades. Nicholas Smyth led one of the sorties:

“When I arrived at Waterfoot we had to crawl for about 300 yards to get to the position held by Scallon and his men. He was under heavy cross fire from two sections of the enemy. I suggested to Scallon that we should try to move into a position directly between the enemy positions in order to get them to fire at each other in their efforts to reply to our fire. We did this and it worked out as we had anticipated. When we got them properly engaged in the darkness, we returned to the safety of our trench. Their fire at each other continued for some time and eventually both parties of the enemy evacuated their positions and retreated.”

After hours of futile fighting most of the British forces in Letter were withdrawn by boat to the relative safety of Boa Island.

At the same time as the Pettigo attacks up to 200 USC militiamen crossed from Tyrone into Donegal at the isolated townland of Lettercran, about fifteen kilometres north-east of Pettigo, terrorising the local population along the way (two girls, Bridget McGrath and Susan McNeil, were wounded by marauding members of the same band earlier in the day, alerting local people to their presence). However the USC’s movements, delayed by their destructive forays, had been anticipated and the group was intercepted in an IRA ambush dispatched from Pettigo under the command of John Travers. After a ferocious encounter it beat a hasty retreat with heavy losses into Tyrone, weapons and ammunition strewn behind it. Meanwhile in Pettigo town itself an infantry battalion from the Lincolnshire Regiment, supported by two companies of the South Staffordshire Regiment, made a frontal – and ultimately futile – night-assault on the village in scenes of near chaos.

On the morning of June 4th, a Sunday, several armoured cars led a surprise British infantry attack on Pettigo, hoping to breach the barricaded road and bridge crossing the Termon River into the village. However the driver of the lead vehicle, a USC man, was almost immediately shot dead, causing his car to flip over and partially block the way. Despite desperate attempts to clear the road the troops behind were unable to advance until artillery was brought up from the 4th Howitzer Battery, Royal Field Artillery. Under a heavy barrage the IRA units were forced to abandon their improvised defences of railway sleepers, carts and barrels, a massed bayonet charge quickly overrunning their positions. Meanwhile another two columns of British troops struggled to encircle the town, but suppressive fire from Irish outposts slowed their advance in the open fields, allowing the main body of Pro- and Anti-Treaty volunteers to stage a fighting withdrawal westward under further bombardment to the wooded hills, while smaller groups were transported by friendly locals across Lough Derg several kilometres to the north-west. During the retreat two volunteers, twenty-three year old Bernard McCanny and twenty-four year old William Kearney, boyhood friends from the same small village of Drumquin in Co. Tyrone, were killed by artillery fire directed at their posts on Billhary Hill, immediately to the west of the village (their bodies were later recovered by the INA and reburied in the Church of St. Agatha, Clar, just outside Donegal Town).

However the small section of IRA volunteers in the machine gun post at Drumhariff Hill, Donegal, just south of the village, continued to resist until they ran out of ammunition, leading to their capture by bloodied and angry soldiers. One of their number, Patrick Flood, a local lad, was shot dead during the fighting while several more were wounded (the next day Flood’s partially buried body was recovered from one of the defenders’ trenches on the hill by a local priest who faced down hostile unionist crowds, reburying the young man in the parish cemetery). A similar dire military situation faced the units defending the Waterfoot which were overrun after two hours of close quarters combat in the marshes. Eventually most of those who fought free of the encirclement at Pettigo were rescued by local residents or INA units in cars and horse-traps, and brought to safety in Donegal Town, some twenty-six kilometres away. There, up to fifty wounded and exhausted men were temporarily sheltered in the old workhouse, attended to by doctors and nurses.

After four years of repeated military humiliations in Ireland the newspapers in the UK reflected the sense of triumphalism felt by many in the imperial corridors of power:

“LONDON, June 6th

LIKE RATS IN A TRAP

MILITARY CATCHES THE REBELS

HIGH EXPLOSIVES IN PETTIGO SALIENT

Gunners Fight Till Wiped Out

The latest Irish telegrams confirm the seriousness of the fighting in the Pettigo Salient, where high explosive shells, machine guns, and bayonets played their part in a battle lasting five hours, which ended in the rout of the Republicans.

A military communique issued at Enniskillen says:—

In consequence of the aggression of the so-called Free State troops in the Pettigo salient it was decided that Imperial troops should occupy the same.

The operations, continued on Saturday and Sunday by land and water, resulted in the military occupying the salient for about a mile from the frontier in order to secure the high ground.

The military lost one man killed. The other side is known to have lost seven killed and eleven prisoners.

In order to dislodge the snipers in the hills it was necessary to fire six rounds of high explosive shells.

Later in the same report it was claimed that:

“…Pettigo was taken at bayonet point.

At least thirty Republican troops were killed.

As the British entered the village the Republicans machine gunned them and the British replied with artillery. After the first heavy shell some of the Republicans fled, but the machine gunners continued until wiped out. Four shells fell behind the village amid a party of fleeing Republicans inflicting heavy losses.

British troops secretly landed at Boa Island, and transferred to the mainland in the night time, caught the retreating Republicans in the rear like rats in a trap. After the more timid Republicans had fled to the hills, only a hundred remained to defend the village from a barricade at the end or the bridge. The British rushed the barricade with the bayonet, and captured the snipers. The artillery then joined in.

The countryside is swarming with British soldiers accompanied by Whippet tanks.

While the Republicans showed no violence towards the residents or Pettigo, they looted extensively. Female sympathisers with the rebels entered the local drapers, helped themselves, and paraded the streets in stolen finery.

When the British took possession of the salient every farmhouse displayed the Union Jack. Aeroplanes are now patrolling…”

The Taking of Belleek

Over the next four days – and despite frequent sniping – the British set about securing their positions at Pettigo, carrying out reconnaissance and intelligence gathering operations in the locality. Prisoners were interrogated, often brutally, while the better-informed USC and RIC took revenge on the resident nationalist population through looting and arson. The squadron of Bristol F.2 Fighters was used to scout south-westward and reinforcements brought by rail to Enniskillen. The Irish, UK and international press, expecting a major confrontation to take place within the salient by the end of the week, dispatched a flock of correspondents to the region.

“LONDON, June 6th

SINN FEINERS ON THE BORDER.

SUCCESS OF MILITARY

HEAVY FIRING IN BELFAST

Enniskillen reports that many thousands of Sinn Feiners with armoured cars are massing on the border to reinforce the garrison at Belleek. The military now hold Free State territory to a depth of a mile north of Pettigo. It is ascertained that upwards of forty Republicans were killed by shellfire during Sunday’s battle.

Mr. Collins takes a most serious view of the aggression of the British troops. He is demanding a full inquiry, and is not going to London unless specially asked.”

On the morning of Thursday the 8th of June columns of troops from the Lincolnshire and Manchester Regiments, several hundred strong, moved on foot and by vehicle towards Belleek in two flanking movements, one from the north-east along the Pettigo Road and one from the south-east along the Enniskillen Road, with Lough Erne dividing them. Heliographs and signal flags were used to keep in contact across the waters of the lake, while a flotilla of commandeered boats moved back and forth. Hazel Valerie West, having joined the patrolling of Lough Erne to prevent aid reaching the isolated defenders, was again in the action, this time from a militia HQ on another island in the lake, just south-east of Magheramenagh:

“The famous woman “admiral,” Mrs. Laverton, assisted aboard Ulster’s “flagship” Pandora (her private yacht), with a base near Rough Island, and with a flotilla of motor launches in her wake, packed with armed men ready to land on the beach in front of Magherameena [Magheramenagh] Castle, the stronghold in Ulster territory, recently seized by the rebels.”

In the event the castle and its environs were taken without incident, the garrison having been withdrawn the previous evening, though it did not prevent some reporters claiming its storming as a great act of valour. Around noon a British armoured car entered Belleek itself and was almost immediately fired upon by units dug-in near the local schoolhouse, thus providing the excuse the expeditionary leaders required to launch a full-scale assault.

As the British soldiers advanced westward they came under rifle and machine gun fire from IRA volunteers stationed in the vicinity, particularly the depleted garrison at Belleek Fort, across the River Erne. Flares fired by the leading parties singled the artillery to open up, several 18-pounder shells hitting the fortified hillock, while more landed in the surrounding fields. After less than an hour of fighting the Irish forces withdrew to a defensive line nearly two kilometres to the west while their former positions continued to be bombarded for a further sixty minutes. By the late afternoon both sides of the townland were under the control of the UK forces, the Tricolour above the smoking fort replaced with a Union Jack, while troops posed for the press cameras.

Afterward

Though isolated exchanges of gunfire between the Irish and British forces continued for several more days the Battle of Pettigo and Belleek was over. In all it had taken nearly fifteen hundred British troops, paramilitary police and militiamen up to a fortnight to overwhelm less than 150 volunteers of the Irish Republican Army/Irish National Army, a combined body of Anti- and Pro-Treaty IRA units. It was, in many ways, the last great battle of Ireland’s early 20th century War of Independence. In the immediate aftermath of the confrontation the local nationalist community was subject to a campaign of terror by elements of the British Occupation Forces, residents abandoning their homes and farms to join the swelling numbers of families fleeing “southward” (following the fall of Pettigo over a 1000 “Roman Catholic” refugees had been evacuated to the city of Glasgow from Belfast where unionists had gone on a celebratory rampage).

Meanwhile the international press reported dozens of deaths and injuries resulting from the thirteen-day battle, though there were in fact only four acknowledged fatalities on the Irish side, including William Deasley from Dromore, Co. Tyrone, who died from gunshot wounds despite reaching the workhouse at Donegal Town (he was buried alongside his two INA comrades in nearby Clar). British casualties were never officially acknowledged – unsurprisingly given the political and military sensitivity of the subject during a low-point in Dublin-London relations – though they were generally believed to be higher. At the same time nearly fifty captured men, Pro- and Anti-Treaty IRA as well as officially INA, were dispatched as prisoners to the city of Derry and elsewhere. Some of these were not to see their freedom until 1924.

For most civilian members of the Provisional Government – unaware of the joint-offensive against the “Orange junta” in Belfast – the clashes in Fermanagh-Donegal were an embarrassment, and a sign of things spiralling out of control. For the military members of the administration, notably Michael Collins as the chairman, the losses in men and territory represented another failure in his supposedly more assertive and unifying northern policy.

In UK circles the unionist leaders saw the two weeks of violence as a justification for their ethno-religious paranoia, while Winston Churchill used his “victory” on the “Irish frontier” to persuade his sympathetic cabinet colleagues to demand more action of the Provisionals against the authority of the republican government (ignoring Lloyd George’s dismissal of the whole affair as a “great bloodless battle“). Indeed the colonial secretary saw the events at Pettigo and Belleek as the military template that Michael Collins and his administration needed to follow in order to liquidate domestic opposition to the treaty, particularly after the assassination of Sir Henry Wilson, one of the architects of the “Orange terror“, outside his London home on the 22nd of June 1922. While the authorities and newspapers in Britain and Ireland blamed the shooting on the anti-treaty IRA Collins knew better. The two captured assassins were almost certainly serving volunteers of the pro-agreement section of the London Brigade of the Irish Republican Army and were under his orders. The INA commander had decided to execute the former field marshal when it was discovered that Wilson was urging unionist leaders to emulate the “successes” in Fermanagh and launch a major offensive against nationalists across the north of Ireland. Collins was to spend the next several weeks trying to organise the rescue of his men – vice-commandant Reginald Dunne and volunteer Joseph O’Sullivan, both aged twenty-four – from captivity in Britain. However events leading up to the internecine blood-letting that was the Battle of Dublin in June and July of 1922 quickly overshadowed his efforts.

Consumed with the need to prosecute a war against former comrades the Provisionals hurriedly – and with little publicity – agreed to the creation of a “neutral zone” in the disputed salient. However this neutrality rested solely on the withdrawal of all Irish troops, the USC and the RIC/RUC from the area, surrendering the territory to the control of the regular British Army. As a result the Free State parts of Pettigo were not freed from occupation until January 1923, while Belleek Fort and its environs were not liberated until August of 1924. Contemporary civilian accounts complained bitterly of the violence and intimidation they suffered from the UK garrisons – notably the Royal Sussex Regiment and the Corps of Royal Engineers – but little action was taken by Dublin beyond some token intergovernmental protests. The “northern” halves of the villages of Pettigo and Belleek, of course, remained under British occupation.

During the autumn of 1922 retribution very nearly caught up with Hazel Valerie West. Having benefited socially and materially from the violence that year her high-handed reputation in Fermanagh made her a prime target for reprisal.

“LONDON, Sept. 18

ULSTER LADY “ADMIRAL.”

ESCAPE FROM KIDNAPPERS.

An attempt to kidnap Mrs. Laverton, who on June 2 rescued from Irish rebels a police garrison on Lough Erne in her yacht Pandora during the fighting at Pettigo, was frustrated by the lady’s promptness in covering the enemy while she ran the gauntlet in a motor-car. Mrs. Laverton has been a marked woman since her Pettigo exploit. Latterly two men have persistently shadowed her. Before the attempt they were seen near the yacht Pandora on Lough Erne. Mrs. Laverton was walking to Lenaghan when she saw an empty motor-car in the middle of the road. The engine was running and Mrs. Laverton was going to investigate when a policeman drove up in a motor-car and warned her that men were lying behind the hedge. Mrs. Laverton drew an automatic revolver, entered the police motor-car, and escaped. The men pursued her.”

In June of 1926 she became the second wife of Augustus William West, a distant relative within the close-knit Ascendancy, and the step-mother to his two children from a previous marriage. They lived in the West’s palatial family residence, Leixlip House, County Kildare, until her death on the 3rd of September 1954. To the end she was unable to accept the existence of a “free” Ireland and like many of her background she simply chose to ignore it.

Note: It is very likely that some of the British artillery and personnel deployed in the Battle of Pettigo and Belleek were used some twenty-one days later by the Provisional Government to bombard the rival republican garrison in the Four Courts complex, beginning on the 28th of June. This of course initiated the Battle of Dublin and the subsequent civil war of 1922-23. This will be examined in a future article.

The town of Belleek filmed by the UK Pathé News following the withdrawal of the British Occupation Forces, 1924. Features shots of the Battery (flying a tricolour) and the bridge across the River Erne that served as the “border”.

Some Sources:

“BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 721

Witness. Nicholas Smyth, 4 Dollymount Ave., Dublin.”

Maps:

A detailed, contemporary map of County Fermanagh from “The Atlas and Cyclopedia of Ireland“, published 1900.

A detailed, contemporary railway map from the “Rail Ireland Viceregal Commission”, published 1906.

New York Times Newspaper Archive:

FIX NEUTRAL ZONE ON BORDER.; British, Ulster and Free State Forces Make Policing Arrangement.

Other Newspaper Archives:

National Library of Australia, Trove, “Pettigo Belleek”

National Library of New Zealand, Papers Past, “Pettigo Belleek”

- This Article is a Finalist In the Best Blog Post category, the Blog Awards Ireland, 2015 *

Fascinating article and very informative

LikeLike

Thanks, BD, quite a lot of research went into it. Trawling through books and newspaper accounts for the last three weeks. Lots more was left out for reasons of time and space. It was exaggerated by contemporaries into a monumental Western Front-like contest, then in reaction to that later historians downgraded it to an inconsequential skirmish (a “tragicomedy” to quote one). However a re-examination of the facts prove that it was a major battle (in a 20th century Irish context, though some civil war confrontations easily surpassed it) and with long-lasting consequences.

It gave Churchill the influence he needed to drag his cabinet colleagues into pushing for civil war in Ireland, via Collins and the Provisionals. His principle opponent was the PM, Lloyd George, who wished to avoid sparking more violence and who was disgusted with the unionists in the north-east and the daily reports of pogroms.

Of course for Churchill, who was involved in dictating every aspect of the campaign in Fermanagh-Donegal, it was a weird sort of ego-militarism, a wiping out of his mistakes at Gallipoli, and a personal validation. The celebrations he held afterwards and the baiting of the Collins-Griffith administration speak volumes.

LikeLike

I was watching a documentary last night about churchill on discovery and during a segment of it about the 1920s era there was old film of what i think was a commonwealth conference or whatever its predecessor was called,and lo and behold there was that bastard cosgrave sitting at churchills right hand in what looked like a group photograph of all the delegates,and right smug the fucker looked too.

LikeLike

Excellent article, féar plé. Hopefully the “decade of commemorations” will lead to more detailed research of this type. For whatever reason there’s a massive lack of good hard information on some of the most crucial incicents in this period.

LikeLike

The post-Truce period in particular is full of gaps. Understandably so. People just didn’t want to discuss such matters and the big dramas of the Civil War took over everything else.

The same way that Fine Gael and FG fellow-travellers cast Cosgrave, etc as saviours of Irish democracy. By selling-out tens of thousands of Irish voters and citizens abandoned to the tyranny of the “Northern Ireland” state. But hush, lets not discuss that.

LikeLike

Excellent article.

D’you mind me asking where did you get hold of some of the photos used e.g. the one of the captured Lancia and of the anti-Treaty IRA with the vehicles? Had not seen those before, though I have seen the ones of the British troops in Belleek / Pettigo. The reason I ask is my granda was a senior Free State army officer in Donegal during this period, I’d love to find out if there’s more photos of that time knocking about, apart from the ones in “Donegal & The Civil War”.

LikeLike

The Belfast Telegraph newspaper archive has a lot of photos relating to 1922 under various headings, principally the 1922 Riots or Ulster Border Trouble/Crisis.

Australia and New Zealand have digitised their newspapers up to the 1930s or so and posted them online. Unfortunately no such initiative has happened here.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on seachranaidhe1.

LikeLike